Bioshock: Infinite Revisited: “Since I Lost You” and other stories

- Post By Jan

- May 17, 2023

There is something eerie, something like an undercurrent in a too-perfect-to-be-real world of Columbia, the game’s cloud city, during the opening sequence of Bioshock Infinite.

Words by Jan Tracz

[A lot of spoilers ahead!]

Such a carefree, utopia-like place seems fake, even fictitious, but it’s mesmerizing enough to stroll through for a few minutes and admire some neoclassical architecture. In Bioshock: Infinite, we play as Booker DeWitt, a private detective who sets out to find a young woman, Elizabeth. It’s a matter of life and death for him – he has debts, so he will either take the job or be seriously punished. When he enters the floating city, Columbia, nothing will be the same for him. At first, Columbia seems like a rather non-invasive demonstration of American uniqueness. In Bioshock’s preludium, when Booker finds himself in this strange city-state, there is one tiny novelty that alarms us and makes the player more attentive to future hints.

At first, we learn that the action is set in 1912 (and yet, it is entrenched in a steampunkish aesthetic, later explained by the game’s plot twists, leading to one massive giddiness). While sauntering through Columbia’s Town Centre, we, as Booker, all of a sudden hear a Barbershop Quartet – a group of hectic singers wearing red stripes jackets and, somewhat suspiciously, reminding us of a quartet from a classical musical, The Music Man from 1962. They’re stylish, cheerful and jovial – so why do we care in the first place? Because, through Booker’s ears and eyes, we hear them singing God Only Knows, a classic hit from 1966…

Columbia full of life – the prophet’s statue (Bioshock Infinite)

I remember playing this game for the first time a few weeks ago – although nothing really scary was happening at the opening sequence’s very moment, I suddenly felt shivers that this idyll would end within a second. The joyful atmosphere was seeping through the screen, but it was mainly the unease that could have been felt – after the first fifteen minutes, we want to leave this city straightaway. I immediately knew there is some surreptitious secret hidden in the heart of Columbia; a mystery concealed under a veil of uncanny deceit, of an idealized arcadia led by the city’s ultranationalist prophet, an almost mythical figure, Zachary Hale Comstock. I read the song’s appearance as one of the very first portentous moments which would, later, happen in the guileless society of Columbia.

God Only Knows covered by Barbershop Quartet (Bioshock Infinite)

We don’t understand why we hear The Beach Boys’ song, recorded fifty years later from the game’s time of action, but it is one of a few subliminal distresses that will affect our future perception. From this moment, we realize that Columbia is a limbo, adroitly arranged as America’s promised land (we read Columbia as an idealized American city). Furthermore, during our walk, we spot one of the signs: “Hear the music of tomorrow…today!” There are no coincidences in this game – there are only warnings. We will later find out that Comstock, with the help of Rosalind Lutece, a genius physicist, opened gates to other (parallel) universes and various time spans through her innovative device. Interestingly, she will later regret that and she will be the person responsible for sending Booker to Columbia. Obviously, it explains why we hear this particular song in 1912 – Comstock insolently stole it! When calling himself a prophet who foresees the future, he, actually, was telling the truth. It explains the city’s technological advancements and prosperity: this is why it is “steampunkish” and does not entirely fit the actual development of 20th century American cities.

Fifth Avenue, New York City, between 1908 and 1915 (Detroit Publishing Co.)

Bioshock Infinite is a first-person shooter, which offers effective and confounding storytelling, even if the entire game is strictly linear and, in a superficial matter, is strongly grounded in just moving forward and defeating new waves of powerful enemies. But, I am not here to analyse its dynamic gameplay. For me, personally, one of the finest beauties of this game is its subversive social comment on America’s so-called paradise: Bioshock Infinite can be read as an astute satire in the form of an audio-visual allegory. We have already mentioned Columbia, a utopian dream. Even the city’s highlights and wonders echo United States’ history: American flags flutter practically everywhere; we visit the Hall of Heroes, which serves as a museum cultivating American generals and presidents; we fight with Patriots, automatons built with the likeness of figures like George Washington or Abraham Lincoln; we watch propaganda films through a silent movie device called Kinetoscope (it augments our immersion); or we encounter brainwashing posters, referring to the national personification of the United States, the one and only Uncle Sam.

Motorized Patriot resembling George Washington (Bioshock Infinite)

Apart from the city’s pivotal infrastructure, we meet Comstock, a prophet-like figure who resembles some Nazi-conservative politician fulfilling his mad, mad vision (in Bioshock, he is the leader of a ultra-nationalist party called The Founders). In reality, he was, presumably, based on a 19th century American Politician, Anthony Comstock, dedicated to endorsing Christian morality. Having someone like this as the city’s “president” only means trouble – racism towards black and Irish groups, poverty and the concept of the Aryan race are on the agenda in Columbia. This is why the group called Vox Populi, a militant group fighting for better days. While they are in conflict with Comstock, their radical approach does not make them necessarily better…

The conjunction of steampunk and patriotic aesthetics (Bioshock Infinite)

Trying to escape from Columbia and saving Elizabeth, meeting all the characters and understanding their goals and roles in this jigsaw puzzle is, honestly, not enough; it is only a halfway house, as the real gamechanger reveals itself, apparently, in the concluding chapter of Bioshock: Infinite. In the last fifteen minutes of the game, we learn the most shocking revelation: Booker and Zachary were the same person/s (I will explain this notion in a minute or two) and everything that happened was a chain reaction of his/their life choices. This revelation is believed to be one of the most controversial plot twists of all time, in a video game. A few delicate hints foretold it, but no one could have known it during the first playthrough.

Zachary Comstock (Bioshock Infinite)

Bioshock: Infinite reveals a recurrent theme of paying various debts for the deeds from the past; firstly, DeWitt “sells” his daughter to Comstock to pay financial debts (but, we can still read it as a “stealing”); later, he pays his debts for Anna by saving her in Columbia; in the parallel universe, Booker resurrects himself as Zachary to pay his war debts and free himself from his guilt (and, possibly, PTSD); in another storyline, he sacrifices for Vox Populi’s cause (pays his debts to them?) and becomes a real martyr. It is a critique of taking some shortcuts – when Booker goes through a baptism after participating in the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901), it is an easy scheme for him.

An exhibition about Boxer Rebellion in the Hall of Heroes (Bioshock Infinite)

By changing his name to Zachary Hale Comstock, he immediately “forgot” about his previous life and started living as if nothing had happened. When he starts getting older and becomes infertile (due to contact with the other universes), he decides, just like that, to bring Anna, his daughter (whom he cannot have in Columbia and whom Booker had, because he hasn’t become the infertile Comstock), without thinking of any repercussions. He behaves like he deserves everything.

As I write these words, I see how intricate this game could be for someone who hasn’t played it in the first place. In Bioshock Infinite, everything happening in the game revolves around DeWitt (who hasn’t become Zachary in this universe) losing his child, Anna/Elizabeth, to himself (Zachary) from a different universe. The prophet knew his self’s (Booker’s) endurance and was aware that the grief would, eventually, fuel the detective’s hatred and desire to find his stolen child. He created a security system and a warning narration claiming the arrival of a “fake shepherd.” And, when the Lutece twins (Robert is a male version of Rosalind from the parallel universe, which was opened through her device), his employers, wanting to defeat Comstock and fix the harm they did through him, enter Booker’s ramshackle office, he agrees to get the mysterious girl back. At this time, he subconsciously knew that the money was irrelevant here as the financial obligation was already paid when he gave Anna to Comstock; the real debt he owned when he went after Elizabeth was, in truth, to her.

A poster foreshadowing the arrival of the “False Shepherd”. “A.D.” on Booker’s right hand are Anna DeWitt’s initials (Bioshock Infinite)

As the musical theme is strongly embedded in this revisiting review, I called this piece Since I Lost You, a title furtively (until now) referring to one of Genesis’ songs, which also parallels the narrative’s main premise. When we hear Phil Collins tranquilly singing verses like, 'Cause my heart is broken in pieces/ Yes my heart is broken in pieces/Since you've been gone’, we just wonder why it hasn’t appeared in Bioshock as an ending tune for the closing credits. And, if you remember the moment when Booker struggles to “retrieve” Anna from Comstock (when the portal instantly closes), other verses from the song obtain new meanings: ‘I held your hand so tightly/That I couldn't let it go'.

Genesis’ song corresponding with the game (Atlantic Records)

But, I digress: no matter to which universe Comstock belonged, he still, in a tragic way, possessed the same nasty traits (every time he loses his child due to his own wrongdoing, etc.) That being said, the game’s main narrative can be treated as a tangible possibility for Booker to repent, for the first time, and do penance for his past (and future?) sins. Throughout his allegorical crossroad – DeWitt learns about Columbia’s nook and crannies just like Dante in Divine Comedy – he gets an actual chance to meet Elizabeth, save her and make up for the lost time. But, Booker’s alter-ego has done too much evil – when he and Elizabeth start to understand this dismal ascertainment, there is only one way to end the omnipresent suffering. To prevent Comstock’s creation in her (and other) universes, they go back in time to the moment of baptism and she drowns main Booker/Zachary. By this, she eliminates any threats related to the rise of Columbia and stealing Anna from a “good” Booker.

15th-century fresco depicting Dante holding a copy of his Divine Comedy. By Domenico di Michelino (Getty Images)

After this shocker, the real resurrection (a consequence of this poignant drowning) takes place in the post-credits scene. Here, “our” Booker, who gains the memories back, wakes up in his own office and seeks to find Anna in his possession, again. DeWitt’s awareness about the previous events should imply that this is a new universe and there were no debts, no selling, no baptism, no Columbia, no Comstock, no Luteces, no Vox Populi and no Elizabeth (just to underline: Elizabeth was Anna’s new incarnation in the cloud city after she was stolen). It would also mean that Booker should find his daughter safe, in her cradle. However, the image cuts as soon as he enters the room, so we are unsure if Anna is in the cradle or not. If she is, it would mean that the loop has been finally broken. If she is not, then it means that something went wrong in Elizabeth’s estimation. But, why? Was there another event as important as DeWitt’s baptism? The game does not give us an explanatory answer.

Post-credits scene, Booker enters Anna’s room and the sequence abruptly ends (Bioshock Infinite)

Can Booker’s attrition be, finally, over? Bioshock: Infinite leaves this brain-twister unanswered – it’s up to the players, if they believe in another manifestation of the game’s fatalistic determinism. We can read Comstock’s drowning both as one more future event that was supposed to happen, or we can treat it as Elizabeth’s triumph, her first coming-of-age decision, when she – finally – gains control over her life and atoned for her father’s dreadful actions. She erased Elizabeth’s existence (with no Comstock there is only Anna) and became the last ever Elizabeth. But, at the same time, she gave a chance to Booker and his daughter to live happily ever after. But, did she, really? Did the drowning reverse Anna’s faith?

DeWitt’s/Comstock’s drowning (perceived through his own eyes) by Elizabeths from various universes (Bioshock Infinite)

I’m up to a more hopeless interpretation, one echoing Jorge Luis Borges’ The Garden of Forking Paths, where the famous Argentine writer foreshadowed the theory of alternate worlds. In his short story, Borges presents the fate of Doctor Yu Tsun, a Chinese professor, who was a German spy during World War I. He visits and learns about his ancestor’s belief that all possible outcomes of one event can occur simultaneously and even interfere with each other; that they can happen in various spheres (universes, when it comes to Bioshock). It was called the riddle of The Garden of Forking Paths. In his philosophical contemplation, Doctor Tsun believed that “the author of an atrocious undertaking ought to imagine that he has already accomplished it, ought to impose upon himself a future as irrevocable as the past.” Borges, through Tsun’s meditations, explored the many-worlds interpretation: he proposed the belief of how past, present and future times’ actions are combined and affect each other.

Does this mean that Booker’s and Elizabeth’s confidence that there is a place, in the time and space continuum where they can find family contentment, will truly fulfil their dream? Their own “atrocious undertaking?” Or, is their aplomb only wishful thinking? “We do not exist in the majority of these times; in some you exist, and not I; in others I, and not you; in others, both of us,” hears Ts'ui Pên's descendant and ponders on this contention, but we understand – after playing Bioshock – what Borges exactly meant. Rewatching the post-credits scene made me concerned, almost bothered that my favourite characters will never find a way out of this loop. It feels like the ominous aura is still there and Booker’s faith is somewhat irrevocable. Such reading of the final scene suggests that there are other events in the (anti)hero’s life which will lead to the birth of a persona similar to Comstock; one who will, sooner or later, take away Anna from DeWitt. To paraphrase Borges’ writing, in some universes, Comstock exists, in some Comstockean figure replaces him. But, Bioshock offers an open ending, so my deliberation is contingent on the player’s speculative reading.

The collage of Jorge Louis Borges, his cat and an ivory labyrinth (Art Share L.A.)

Seemingly, if we use Immanuel Kant's philosophy, a universe where DeWitt doesn't lose Anna is a "noumenal realm" for him and his daughter. It’s open here for a reason (he subconsciously wants to enter it, but does not know if it truly exists), it's standing there for a reason (he wants to be, finally, happy with her), however, the ending scene implies it is not achievable for Booker. Although DeWitt is not fated to be debarred from this realm, he is still not capable to enter it. Is Booker's moral goodness not enough to enter the desirable realm of all realms? The "realm of ends?" Between DeWitt and the happy life scenario, there is a barrier – it is externalized by his inherent evilness, his choosing, as Stanley Cavell puts it, to "thwart the very possibility of the moral life." So, to present it in other words, rescuing Elizabeth in one lifetime (in one universe) wouldn’t, alas, exempt him from suffering, in the end. This realm is unexperienceable because DeWitt is not a perfected version of himself – and he will never be, as his past and the future are always brimming with morally ambivalent decisions.

Immanuel Kant, print published in London, 1812 (Getty Images)

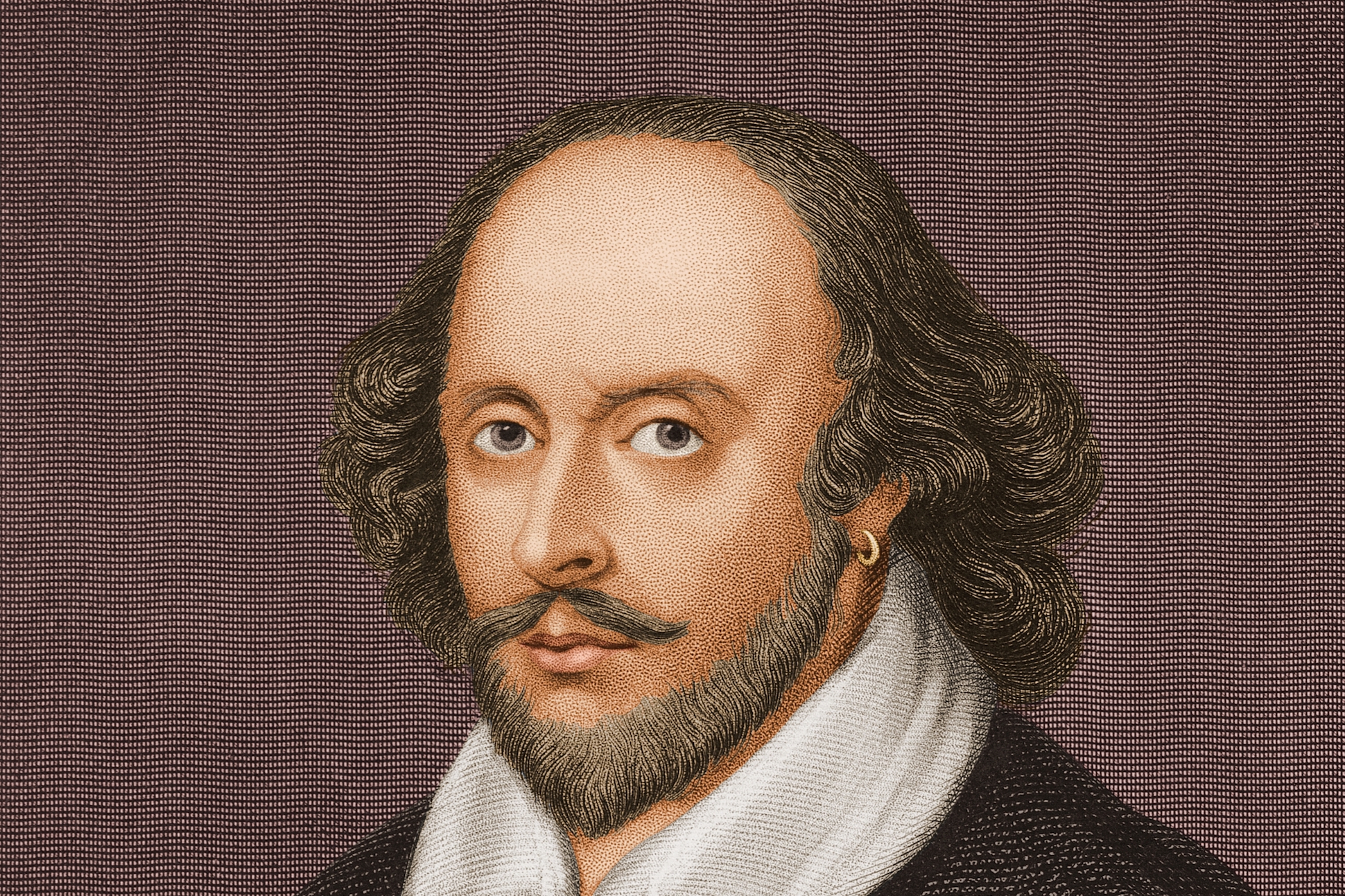

Completing Bioshock Infinite exposes our own fears that William Shakespeare was, apparently, right and our entire existence is one theatrum mundi – we put on the masks and become new pawns on an infinite scene of being. The game proposes a story strongly relying on deterministic tenets, so one constantly wonders if our heroes can, ultimately, alter their impending fates. It asks us: to what extent are we able to affect anything that is, eventually, going to happen?

William Shakespeare, circa 1600 (Getty Images)

In any case, it’s a first-person shooter even for people who only yearn for exceptional storytelling and detest a repeatable shooting experience. Just like Booker, we arrive in Columbia with no reckoning, but leave with more questions than answers. Staying in this cloud city involves us in flirting with life’s vicissitudes – you never know what awaits around the next corner.

P.S.

By the way, it works both as a separate story, but also as a cleverly-made prelude to the first Bioshock (if you play a two-part DLC, Burial at Sea). But, the add-on’s plot with its own intricacies, taking place in a parallel universe – the game changes Columbia for Rapture (!) from the first Bioshock – is a tale for another time.

Elizabeth appearing in Rapture (Bioshock: Infinite, Burial at Sea)